Prior to 1890, individual states, rather than the Federal Government, regulated immigration into the United States. Castle Garden (now Castle Clinton), located in the Battery of Manhattan, served as the immigration station for the Port of New York from 1855 to 1890. Approximately eight million immigrants passed through its doors, mostly from Northern European countries; this constituted the first large wave of immigrants to settle and populate the U.S.

In the 1800s, rising political instability, economic distress, and religious persecution plagued Europe, fueling the largest mass human migration in the history of the world. With the passing of the Immigration Act of 1891, it became apparent that Castle Garden was ill-equipped and unprepared to handle the mass influx, leading the Federal government to construct a new immigration station on Ellis Island. During construction, the Barge Office in the Battery was used for immigrant processing.

The new facility on Ellis Island began receiving immigrants on January 1, 1892. Annie Moore, a teenage girl from Ireland, accompanied by her two younger brothers, made history as the very first immigrant to be processed at Ellis Island. Over the next 62 years, more than 12 million immigrants would arrive in the United States via Ellis Island.

Most immigrants entered the United States through the Port of New York, although there were other ports of entry in cities such as Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, San Francisco, and New Orleans. The great steamship companies like the White Star, Red Star, Cunard, Holland America and Hamburg-America Lines played a significant role in the history of Ellis Island and immigration as a whole.

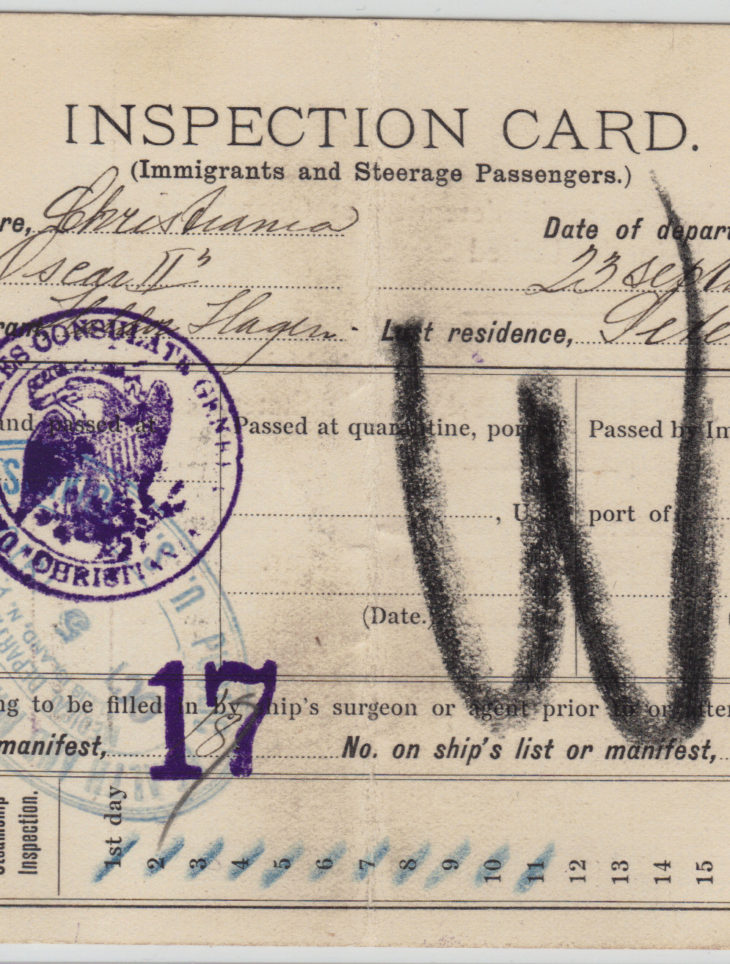

First and second class passengers arriving in New York Harbor were not required to undergo the inspection process at Ellis Island. Instead, these passengers received a cursory inspection aboard the ship; the theory being that if a person could afford to purchase a first or second class ticket they were affluent and less likely to become a public charge in America due to medical or legal reasons. However, regardless of class, sick passengers or those with legal problems were sent to Ellis Island for further inspection.

This scenario was far different for third class passengers, commonly referred to as “steerage.” These immigrants traveled in crowded and often unsanitary conditions near the bottom of steamships, often spending up to two weeks seasick in their bunks during rough Atlantic Ocean crossings. After the steamship arrived in the Harbor, steerage passengers would be placed aboard a ferry or barge and brought to Ellis Island for their detailed inspection.

During the early morning hours of June 15, 1897, a fire on Ellis Island burned the Main Immigration Building of the immigration station completely to the ground. Although no lives were lost, Federal and State immigration records dating back to 1855 burned, along with the pine buildings that failed to protect them.

The U.S. Treasury quickly ordered the immigration facility be rebuilt, under one very important condition: all future structures built on Ellis Island had to be fireproof. In the interim period, the Barge Office in Battery Park was again used to process immigrants. On December 17, 1900, the new Main Building was opened and 2,251 immigrants were received that day.

Although ship manifests were burned for entries prior to June 1897, Customs Lists remain. These records were kept safe in the U.S. Customs Office. So while the Foundation’s Passenger Search does not include ship manifests for years prior to 1897, Customs Lists for those passengers are available to view! Quite similar to a ship manifest, these records detail each passenger’s name, age, country of origin, as well as how many pieces of luggage they carried. Search here!

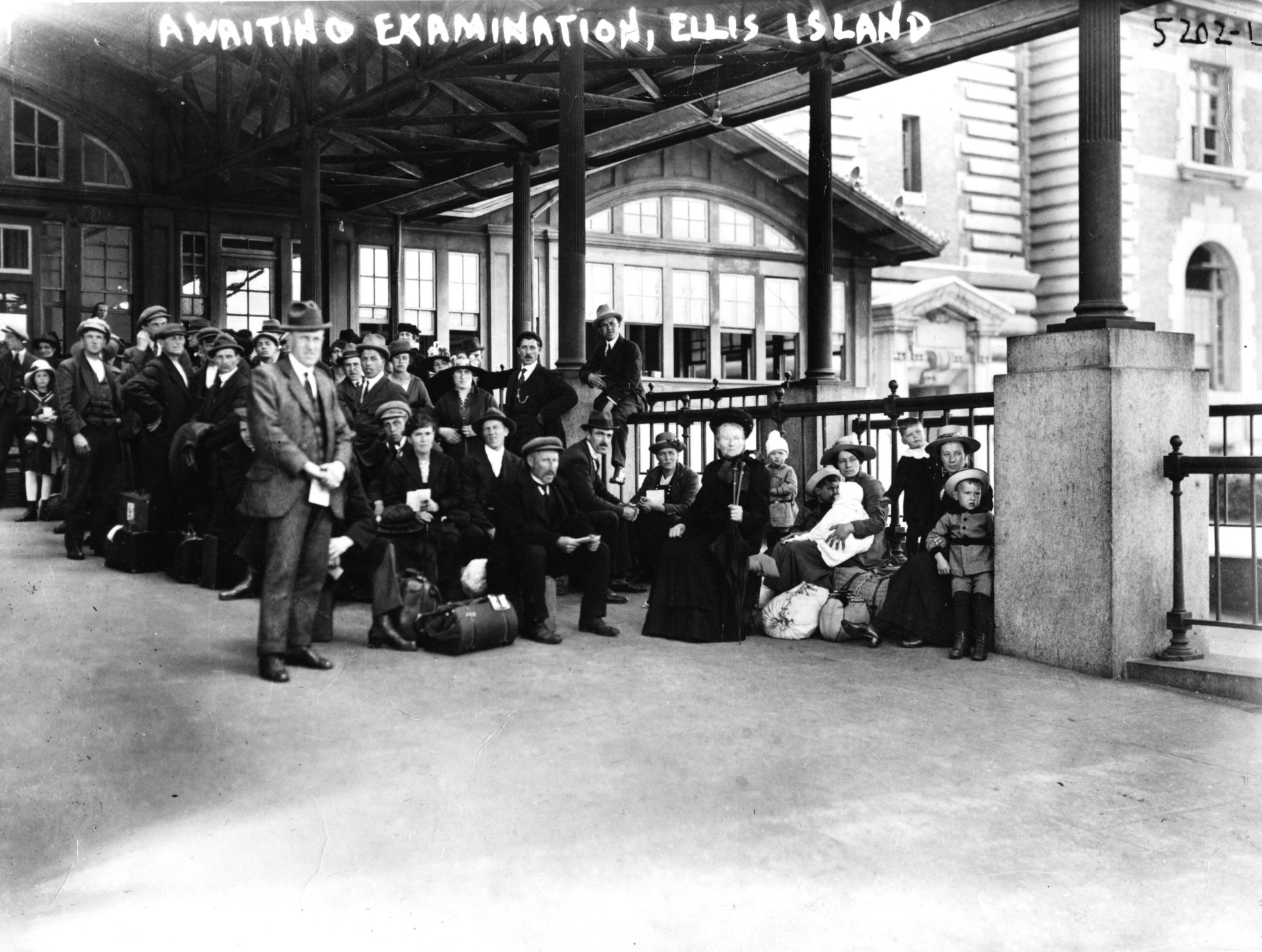

If an immigrant’s papers were in order and they were in reasonably good health, the Ellis Island inspection process lasted 3 to 5 hours. The inspections took place in the Registry Room (Great Hall) where doctors would briefly scan every individual for obvious physical ailments. Doctors on “the Line” at Ellis Island soon became very adept at conducting these rapid inspections.

The ship’s manifest, initially filled out at the ship’s port of departure, contained the immigrant’s name and answers to a series of questions regarding the details of their origin, destination, and their likelihood to become a public charge. This document was used by the legal inspectors at Ellis Island to cross-examine during the legal inspection. Contrary to popular belief, interpreters of all major languages were employed at Ellis Island, making the process efficient and ensuring that records were accurate.

Despite the island’s reputation as an “Island of Tears” the vast majority of immigrants were treated with courtesy and respect, free to begin their new lives in America after only a few short hours on Ellis Island. Only two percent of the arriving immigrants were excluded from entry. The most common reasons for exclusion were a doctor diagnosing an immigrant with a contagious disease that could endanger the public health, or a legal inspector being concerned that an immigrant would likely become a public charge or an illegal contract laborer.

In the early 1900s U.S. immigration officials mistakenly thought that the peak wave of immigration had passed. To their surprise, immigration was on the rise. In fact, 1907 marked the busiest year at Ellis Island with over one million immigrants processed.

From the beginning of the mass migration period that spanned 1880 to 1924, a relentless group of politicians and nativists demanded increased restrictions on immigration. A literary test, the Chinese Exclusion Act, the Alien Contract Labor Law, quota laws, and the National Origins Act were among the regulations enacted to limit who could enter the U.S., with restrictions based upon the number of ethnic groups already living in the country. As a result, Ellis Island experienced a rapid decline in usage beginning in the early 1920s.

The island served a different purpose during the First World War. Both the United States Army and Navy established bases on Ellis Island. The Army utilized the Main Immigration Building, while the Navy utilized the Baggage and Dormitory Building.

After World War I, U.S. embassies were established in countries all over the world. The necessary paperwork and medical inspections were completed at the consulate, quickly replacing the Ellis Island inspection process.

After 1924, the only passengers brought to Ellis Island were those who had problems with their paperwork, were suspected of having a contagious disease, as well as war refugees and displaced persons needing assistance. Ellis Island remained in use for three more decades serving a multitude of purposes. During the Second World War, the United States Coast Guard established a base, training some 60,000 Coast Guard members on Ellis Island. In addition, Japanese, German and Italian nationals suspected of being enemy aliens were brought to Ellis Island to be interned.

In November of 1954, the last remaining detainee on Ellis Island, a Norwegian merchant seaman named Arne Peterssen, was released and Ellis Island was officially closed by the U.S. government.